Jorge Luis Borges, a blind librarian who became the most influential short-story writer ever to emerge from Latin America, was born in Buenos Aires. Prosperous but not rich, his family was prominent in Latin American history and included several famous military heroes. Borge’s Protestant father and Catholic mother reflected Argentina’s diverse background; their ancestry included Spanish, English Italian, Portuguese, and Indian. Moreover, Borge’s British grandmother lived with the family, so “Georgie” and his younger sister were raised speaking both English and Spanish.

Borges did not attend school till he was nine but was taught at home by a British governess. His gentle and erudite father, who practiced law, encouraged his precocious reading. “If I were asked to name the chief event in my life.” The author later commented, “I should say my father’s library.“ Borges’s early literary enthusiasms included H.G. Wells. Robert Louis Stevenson, Edgar Allan Poe, and Miguel de Cervantes (whom he first read in English).

In 1914 the family traveled to Europe to seek medical treatment for Borges’s father, who was going blind (a congenital condition his son would in inherit). They planned to stay a few months, but were trapped by the outbreak of World War I. Settling in Switzerland, they sent the fifteen-year-old Borges to a French-speaking school. He graduated in 1918 but never attended university. The family then moved to Spain where Borges, who was now writing poetry, joined the Ultraists, a group of avant-garde writers and artists.

Borges returned to Buenos Aires in 1921 and began publishing poems and essays. He also edited two small literary magazines, one of which was printed as a poster that was affixed to public walls. In 1937 to help support mother and dying father, the thirty-seven-old Borges (who still lived at home) got his first job as an assistant librarian. He had already published seven books of poetry and criticism but has only just began writing short stories. Over the next fifteen years he published most of the stories that would win international acclaim–collected in four volumes, A Universal History of Infamy (1935), The Garden of Forking Paths (1941), Ficciones (1944), and The Aleph (1949).

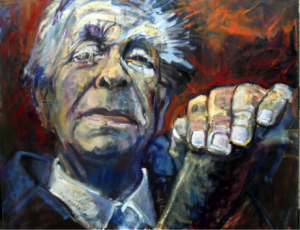

During the decisive decade Borges encountered political trouble. Having signed a manifesto criticizing the Argentine military dictator Juan Peron, the author was fired from his library post in 1946 and appointed (as an insulting joke) chicken inspector in the public market. He refused the position and supported his mother and himself on his meager literary earnings until Peron’s outer in 1955, when the now blind author was appointed director of the National Library. In a celebrated poem Borges noted “that with magnificent irony / God has given me these books and darkness at one stroke.” Unable to write, he now dictated his work to his elderly mother. Gradually his literary interests shifted back to poetry since poetry was harder to compose without recourse to paper.

Borges’s international reputation really began only in 1961 when he shared (with Samuel Beckett) the Prix Formentor, a major international literary prize created by six avant-garde publishers. Ficciones was then simultaneously published in Italy, Spain, Germany, England, and America. (A French edition had appeared a decade earlier.) Borges’s work had an electrifying effect on younger writers. Almost immediately he became the representative figure of postmodernism. His work has a seminal influence not only among Latin American writers like Julio Cortazar and Gabriel Garcia Marquez but also non-Hispanic writers as diverse as Italo Calvino, Milan Kundera, Umberto Eco, John Barth, Angela Carter, and Salman Rushdie.

Borges, who had ventured no further than neighboring Uruguay after 1924, spent his later years traveling widely as an international literary celebrity, In 1961 he accepted a visiting chair at the University of Texas, the first of many academic appointments. In 1967 he married a widow whom he had courted in his youth, but the couple soon divorced. Borges was diagnosed with cancer in 1985 and moved to Geneva (where he had spent his adolescence) for treatment. On his deathbed he married his traveling companion a former student, who had helped him through his last years.

In international terms Borges is the most influential short-story writer of the last half century. Umberto Eco ranked Borges with James Joyce as one of the two great writers of the second millennium. Mario Vargas Llosa declared him “the most important Spanish language writer of modern times.” Borges’s work both expanded the possibilities of contemporary fiction and changed perspectives on the literary past. One might summarize Borges’s main achievements in two ways. First, he found a way to combine the accessible pleasures of traditional genres (such as the supernatural tale, detective story, fantasy tale, or gaucho legend) with the intellectual complexity of experimental fiction. Borges employed these popular forms, which other avant-garde writers would have rejected as hopelessly old fashioned, but underneath the engaging story, he created a second but more ambiguous and intellectual narrative that questions but never quite negates the surface plot.

Borges’s second major innovation was to take conventional nonfiction forms (such as the book review, biographical sketch, encyclopedia entry, or scholarly article) and use them as fictional devices. Borges, for example, often reviewed nonexistent books. Mixing real information with sheer invention, he recounted imaginary plots or fictional biographies in a form that readers associated with factual exposition. These pseudo-essays allowed him to explore metaphysical paradoxes and historical mysteries in the compressed and evocative form of short story. Mixing fact with fancy also allowed Borges to create fictional commentaries on earlier literature in ways that offered interesting new perspectives.

Brevity was the soul of Borgers’s genius. He never attempted a novel. “It is a laborious madness and an impoverishing one.” Borges wryly commented in his foreword to Ficciones, “the madness of composing vast text books—setting out in five hundred pages an idea that can be perfectly related orally in five minutes. The better way to go about it is to pretend that these books already exist, and offer a summary, a commentary on them.” By this method Borges created a vast library of imaginary volumes and freshly reinterpreted real one that have fascinated readers for half a century.