By: Ellie Burgueño, Journalist and Writer.

By: Ellie Burgueño, Journalist and Writer.

“Man is an experiment; only time will reveal whether he was worth the risk.” What a profound truth hidden within those words. As more details surface from what was concealed for decades in the Epstein files, one cannot ignore the disturbing pattern of moral collapse. Some men, entrusted with influence and power, did not rise to their promise — they descended beneath it. They abandoned conscience for appetite, integrity for indulgence, and humanity for unchecked impulse. In doing so, they revealed not strength, but weakness; not superiority, but spiritual emptiness. History does not simply expose actions — it exposes character, one that is rotten.

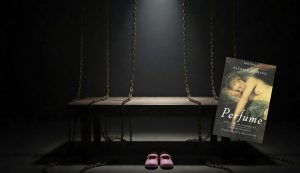

As an avid reader, I have long been fascinated by stories the world embraces as fiction — tales so dark and extravagant that we comfort ourselves by believing they could never be real. One of those books found me when I was only ten years old: Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, written by Patrick Süskind.

Published in 1985, the novel became an international bestseller, translated into more than 50 languages and selling millions of copies worldwide. It was praised as literary genius — haunting, imaginative, grotesque. Fiction, we were told.

The story centers on Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, a man born without a personal scent, abandoned at birth, deprived of affection, invisible to society. Yet he possesses an extraordinary gift: a supernatural sense of smell. From the margins of existence, he discovers that human desire is governed not by logic, but by the senses. Determined to master this invisible power, he apprentices as a perfumer and learns to distill aroma into obsession.

Then comes the chilling revelation: the most intoxicating fragrance he has ever encountered is the scent of a young girl. Convinced he can capture innocence itself in a bottle, he becomes a murderer — killing adolescent girls to extract their essence in pursuit of the “perfect” perfume.

For decades, readers treated this as allegory. A metaphor about vanity, desire, and moral decay. A grotesque fantasy.

And yet, as disturbing revelations have surfaced in the files surrounding Jeffrey Epstein, the boundary between fiction and reality has grown alarmingly thin. Allegations tied to Epstein and his network describe not only systematic exploitation and trafficking of minors, but also a culture of ritualized abuse, manipulation, and moral corruption hidden behind wealth and influence. While claims of “satanic cults” and ritual practices remain largely in the realm of accusation and conspiracy, what is documented and undeniable is the organized abuse of underage girls and the decades-long silence that has shielded perpetrators — a silence now fracturing as more documents emerge and survivors demand justice.

But Epstein’s case, horrific as it is, is only one manifestation of a much larger global crisis — one that ensnares millions of children and vulnerable youth across continents. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, recent detections of human trafficking show a 31% increase in child victims since before the COVID-19 pandemic, and children now represent approximately 38% of all trafficking victims detected worldwide.

The numbers are staggering: globally, an estimated 1.2 million children are trafficked every year for sexual exploitation, with a majority of them under 18. Girls are disproportionately affected — making up approximately 71% of trafficked children — while boys often fall prey to forced labor and criminal exploitation.

Human trafficking is not an abstract phenomenon. It is the third-largest criminal enterprise on Earth, behind only drugs and arms, generating tens of billions of dollars in illicit profits. Its reach extends from Southeast Asia — where the average age of child victims is as young as 16 — to Africa, Latin America, Europe, and North America. In the United States alone, studies indicate that sex traffickers frequently target children between the ages of 12 and 14, and that cases have been documented in all 50 states.

Behind these numbers are young girls and boys whose lives are stolen in silence — victims of grooming, deception, coercion, and often betrayal by those they trusted. They are lured by false promises of safety, jobs, or affection, only to be commodified and sold into routines of abuse and degradation that crush body and spirit alike.

History reminds us this is not new. From ancient cultic rites involving the exploitation of the vulnerable, to aristocratic scandals in Europe, to modern trafficking networks exposed across continents, the commodification of innocence has resurfaced in different forms for centuries. The faces change. The power structures evolve. The pattern remains.

History reminds us this is not new. From ancient cultic rites involving the exploitation of the vulnerable, to aristocratic scandals in Europe, to modern trafficking networks exposed across continents, the commodification of innocence has resurfaced in different forms for centuries. The faces change. The power structures evolve. The pattern remains.

When I revisit Perfume, I can no longer see it as mere fiction. Like much great literature, it may have drawn from the undercurrents of human darkness that persist across time. Writers often magnify what society whispers. They exaggerate what already exists. They fictionalize what is too disturbing to confront directly.

Perhaps Süskind did what many authors do: he distilled reality into metaphor. He captured, in grotesque symbolism, humanity’s capacity to objectify, consume, and destroy what is pure — all in the pursuit of power, pleasure, or immortality.

The tragedy is not that such horrors were imagined.

The tragedy is that we are discovering they were never entirely imaginary — they were truths buried for decades, concealed behind power, silence, and complicity.

There have been multiple deaths and questionable suicide cases connected to the Epstein investigation, circumstances that have fueled suspicion and deepened public distrust. To date, approximately 3.5 million pages of documents, along with thousands of videos and images, have been released, and many more remain under review — a grim reminder that the full scope of this horror is still largely hidden.

As horrific as these realities may be, a deeper question emerges: What kind of world were we born into?

As a believer in God, I cannot ignore the spiritual dimension this darkness evokes. Allegations of occult or ritualistic practices among powerful elites, though not fully verified, serve as a stark symbol of moral collapse. What is undeniably real is the exploitation of innocence, the corruption of power, and the absence of conscience. When evil manifests so boldly, it forces us to confront the truth of human nature.

Scripture reminds us:

“For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.” — Ephesians 6:12 (KJV)

If evil exists — and history proves that it does — then goodness must also exist. Just as darkness is not a force of its own but the absence of light, evil can be understood as the absence of God, moral truth, and conscience.

And so, the enduring question remains: Is good stronger than evil?

Faith tells us that light does not struggle to exist; it simply shines, and darkness retreats. But light requires vessels — voices willing to speak, hearts willing to act, and courage willing to confront corruption. Perhaps we are not meant to wait passively to see who wins. Perhaps we are called to choose the side of light — and to become part of the answer.